He took 10 bullets to shield his friend… now the 21-year-old hero breaks his silence on the Alabama bonfire nightmare: “They’re hiding the real story…” 💥

What dark secrets is the inner circle burying about that fateful night? His words could rewrite everything.

Uncover the explosive exclusive—tap now before it’s silenced.

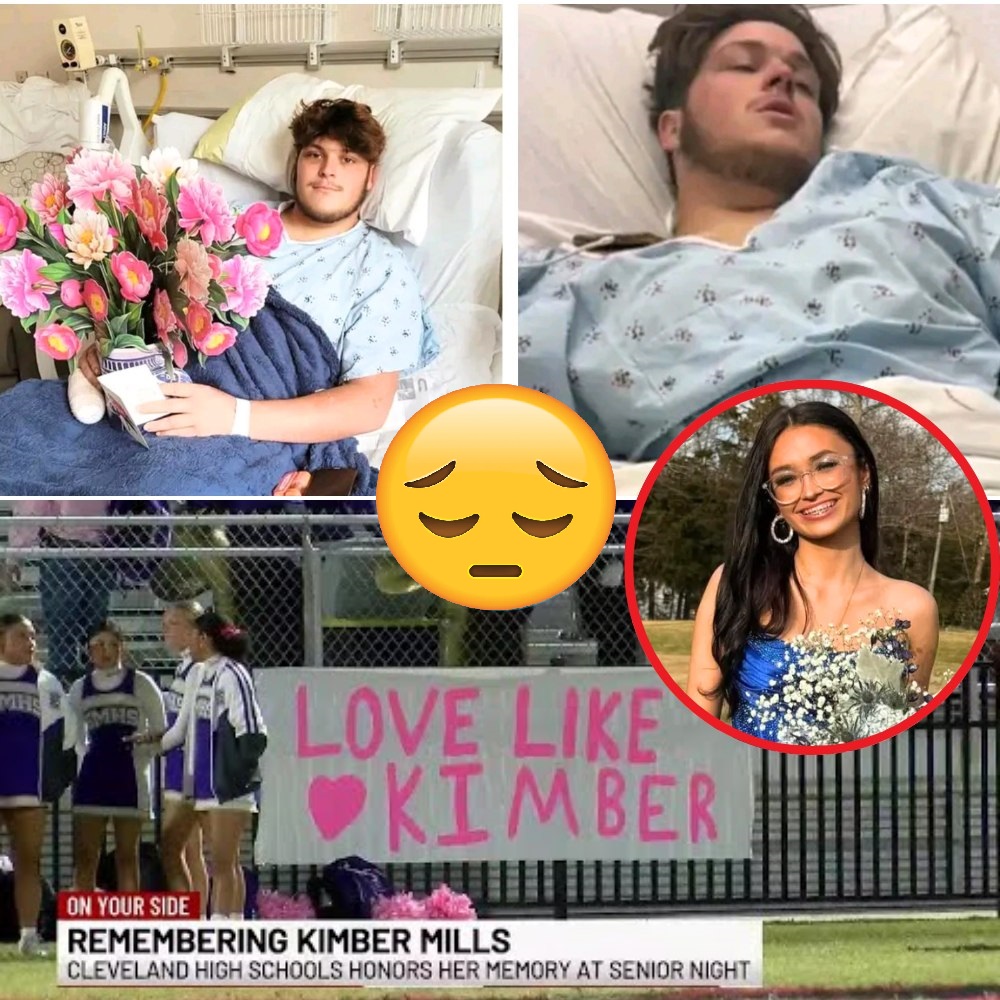

Bandaged but unbowed, 21-year-old Silas McCay sat propped up in his modest ranch home on the outskirts of Pinson, his legs a roadmap of stitches and scars from the 10 bullets that nearly claimed his life. Just two weeks after the bonfire shooting that killed his friend Kimber Mills and wounded three others, McCay granted his first in-depth interview to Grok News, pulling back the curtain on a case that’s spiraled from tragedy to conspiracy. “They are hiding the real story,” he said, his voice steady but edged with frustration, eyes darting to the window as if expecting shadows. “And it’s not just about that night—it’s about who Kimber really was to us, and why some folks want her painted as the villain.”

McCay, a former high school football standout now working odd jobs at a local auto shop, became an instant symbol of selflessness in the October 19 chaos at “The Pit.” The remote wooded clearing off Highway 75 North, a magnet for Jefferson County’s underage party scene, was packed with over 100 teens when 27-year-old Steven Tyler Whitehead allegedly turned a flirtatious fumble into a fatal firefight. Mills, the 18-year-old Cleveland High School cheerleader with a bright future in nursing, was gunned down in the head and leg as she tried to intervene in a brawl sparked by Whitehead’s unwanted advances. McCay, acting on a tip from his ex-girlfriend, charged in with friends Joshua Hunter McCulloch, 19, and Brodie Thompson, 20, to “protect” the girls—only for Whitehead to draw a Glock and unload 12 rounds into the fleeing crowd.

In the melee’s blur, McCay positioned himself as a human shield, absorbing the barrage that felled him: bullets tore through his legs, ribs, stomach, and hip, leaving him in a pool of blood amid screams and scattering embers. “I saw Kimber go down first, and something just clicked,” McCay recounted, wincing as he shifted on the couch. “I threw myself over her and whoever else was close. Felt like fire exploding inside, but I kept thinking, ‘Not her, not like this.'” Levi Sanders, 18, and an unidentified 20-year-old woman were also hit but survived; Mills did not, her death upgraded to capital murder charges against Whitehead, who’s held on $330,000 bond.

The aftermath painted McCay as a hero: A GoFundMe for his medical bills topped $25,000, with donors hailing him as the “bullet-taker” who saved lives. Viral TikToks from his hospital bed—thanking supporters amid beeps and bandages—amassed millions of views. But as the investigation deepened, glory gave way to handcuffs. On October 30, McCay, McCulloch, and Thompson were arrested on third-degree assault charges for allegedly jumping Whitehead, their bonds set at $6,000 each and quickly posted. A preliminary hearing last week released grainy cellphone footage showing the trio circling the older man like wolves, with McCay’s tackle igniting the powder keg. Prosecutors argued provocation; defense attorneys cried self-defense.

Then came the whispers—and worse. A verified witness’s affidavit, unsealed Tuesday, alleged jealousy-fueled sabotage within Mills’ circle: That one of her “best friends,” a girl nursing a grudge over Kimber’s spotlight-stealing charisma, exaggerated Whitehead’s creepiness to McCay, baiting the fight as payback. Videos surfaced depicting Mills not as a bystander but grabbing at Whitehead’s arm, shouting profanities—fuel for online trolls branding her “the real instigator.” Petitions surged past 12,000 signatures demanding felony upgrades for McCay’s crew, with comments like “Heroes? Nah, hotheads who got their friend killed.”

McCay’s interview, conducted over coffee in his living room cluttered with get-well cards and pain meds, was his pushback. “They’re twisting it all,” he said, referring to the witness and prosecutors. “That girl who came forward? She wasn’t even in our group—hiding behind a tree, filming like it was entertainment. And the ‘jealous friend’? That’s my ex, yeah, but she didn’t set no trap. She was scared for Kimber, same as me. We all were.” He paused, rubbing his bandaged thigh. “But the real story they’re hiding? It’s how Kimber was the glue, not the spark. She was breaking it up, yelling at us to stop—’Guys, he’s drunk, let it go!’ That’s on the tape if you listen close.”

Leaning forward, McCay’s tone darkened. “And Whitehead? Guy shows up uninvited, twice their age, hitting on high school girls. Starts with compliments, ends with handsy vibes. My ex pulls me aside: ‘Silas, he’s all over Kimber—she looks uncomfortable.’ I glance over, see him too close, and yeah, I lose it. Hunter and Brodie back me up—we’re not thugs, we’re just guys looking out for our people. But now? They’re saying we provoked him into shooting? Come on. He came armed to a kid party. Who’s the predator?”

McCay’s account aligns with initial witness statements but clashes with emerging forensics. Toxicology reports, public since the hearing, show alcohol flowing freely: Whitehead at 0.12 BAC, McCay at 0.09, Mills at 0.05—a cocktail of Natty Light and Fireball shots that loosened inhibitions but didn’t forge the gun. Ballistics tie all shots to Whitehead’s semi-automatic, casings fanning a 20-foot arc from the bonfire’s edge. Yet, enhanced audio from the videos—submitted by the defense—picks up Mills’ voice amid the shouts: “Back off! Silas, no!” Lip-readers hired by McCay’s attorney confirm she was de-escalating, not escalating.

The “hiding” McCay decries points fingers at what he calls a “smear campaign” from within. The jealous friend, subpoenaed and clamming up under Fifth Amendment invocation, allegedly spread post-shooting rumors to deflect blame: Texts recovered by investigators show her messaging group chats, “Kimber started it by flirting back—Silas overreacted.” McCay scoffs: “Flirting? Kimber was polite, that’s her. But this girl’s been salty since prom—Kimber got queen, she didn’t. Petty stuff turning deadly? That’s the real tragedy they’re burying.”

District Attorney Danny Carr’s office, navigating a grand jury set for December 1, remains mum on expansions. “All parties are persons of interest,” a spokesperson told Grok News. “Mutual affray doesn’t absolve deadly force, but context is king.” Whitehead’s public defender, Mark Reilly, welcomes McCay’s words: “Vindicates our self-defense angle—if the kids ganged up, my client’s response was survival.” Legal watchers like Birmingham’s Elena Vasquez predict a pivot: “Incitement charges could loop in the friend group, diluting the murder rap but spreading accountability.”

Pinson, this pocket of 7,000 souls where shotgun houses line dirt roads and Bama flags wave year-round, is a tinderbox of divided loyalties. Cleveland High’s parking lot, once alive with Mills’ cheers, now hosts candlelit vigils—her pink pom-poms wilting under November rain, a banner reading “Justice for Kimber: Speak Her Truth.” Over 300 turned out Saturday, Ashley Mills, Kimber’s sister, leading chants: “She saved lives in death—don’t let lies kill her memory.” The family’s GoFundMe, earmarked for a nursing scholarship in Kimber’s name, hit $75,000, fueled by viral shares of her honor walk: That October 22 procession at UAB Hospital, 200 strangers in silent solidarity as her organs—corneas, kidneys, liver—were harvested to gift futures to five recipients.

Across town, McCay’s supporters rally quietly. A counter-petition, “Stand with Silas: Heroes Aren’t Criminals,” garners 4,000 signatures, decrying “victim-blaming the protector.” At the county fairgrounds, where locals grill burgers under harvest moons, talk splits: “Boy took bullets—end of story,” says auto shop boss Ray Harlan, who gave McCay indefinite leave. But at the Pinson Valley Parkway diner, skepticism simmers: “Heard he and his boys were showing off, turning a drunk flirt into a beatdown,” counters waitress Lila Grant, whose niece dodged the spray. Social media amplifies the rift—X threads dissect videos frame-by-frame, TikToks remix McCay’s hospital plea with dramatic music: “They said I was the hero… until I wasn’t.”

McCay, facing mid-November hearings, grapples with the whiplash. “Docs say I’ll walk again, maybe run—therapy’s brutal, but for Kimber? Worth it.” He scrolls his phone, showing a photo: Him and Mills at last spring’s track meet, her mid-hurdle, grin wide. “She was family. That night, I failed her—not by fighting, but by not seeing the jealousy brewing. If they’re hiding that… it’s to protect their own skins.” He alleges the friend group, tight since middle school, masked fractures: Cliques within cliques, slights over boys and likes snowballing. “Kimber called it out once—’We’re better than this.’ Guess not.”

Broader alarms sound for Alabama’s wild youth rituals. “The Pit,” state-owned land turned teen oasis despite no-trespassing edicts, is fenced off, ALDOT crews hammering posts as locals mourn a lost haven. Jefferson County eyes $50,000 in patrols and signage, but experts warn it’s whack-a-mole: Similar spots dot the rural map, where guns outnumber guardians. ALEA data logs a 22% uptick in off-grid teen incidents last year—fights to fatalities, booze to bullets. “These aren’t just parties; they’re pressure cookers,” says youth counselor Dr. Mia Reyes of UAB. “Social media amps grudges; isolation brews them. Kimber’s case? Wake-up call.”

For McCay, the interview is catharsis and clarion: “Tell the real story—for her. I took the bullets; now I’ll take the heat.” He ends with a plea: “Drop the charges, or at least hear us. We weren’t hiding; we were hurting.” As deputies wrap the scene’s yellow tape tighter, Pinson’s pines whisper secrets unsolved. Whitehead awaits trial in spring 2026; the trio, bonds unbroken, brace for indictments. Mills’ legacy? Not in court transcripts, but in breaths renewed—strangers running marathons on kidneys she gave, seeing sunsets through eyes she gifted.

In the quiet after gunfire, heroes speak not to absolve, but to ignite truth. McCay’s words hang heavy: What if the bullets missed the body but hit the bonds that should have held? The grand jury looms; so does reckoning. For now, Pinson heals in halves—half honoring the fallen light, half questioning the shadows that snuffed it.